Katy Thompson, Associate Director of Education

Labor Day, signed into law as a formal holiday by President Grover Cleveland in 1894, has its origins in the Industrial Revolution, when the average American worked 7 days a week, 12-14 hours a day, to hit production demands. Labor unions organized to provide living wages and basic safety measures (fresh air, sanitation) through strikes, protests, and rallies. Enacted to honor and appreciate the American labor movement and the laborers whose work was integral to the development and achievements of the United States, it is now a 3-day weekend we fill with picnics, BBQ, and fireworks. There are are multiple forms of labor, and artists have their own. We can easily recognize a construction worker on the job, for example, but what does an artist at work look like?

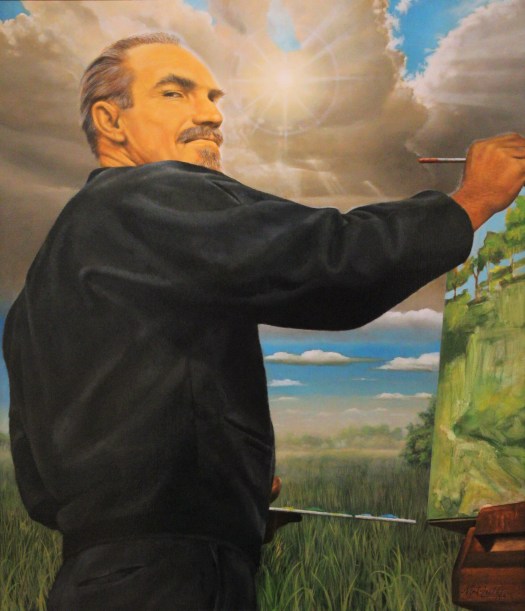

Nancy Lutz, born in Portland, Indiana, is a working regional artist known for her range in subject matter. Alongside her usual landscapes and portraits of Native Americans, she painted portraits of two of her art school teachers, George McCullough (above) and Noel Dusendschon (below). Studying in the 1960s at the Fort Wayne Art School (with fellow classmate and regional artist Gwen Gutwein), these paintings portray these two teaching artists at work.

Above, George McCullough works en plein air, creating one of his signature colorful, loosely painted landscapes. The viewer looks at McCullough from below and, with the sun creating a loose halo of light around his head, Lutz portrays their relationship of a mentee looking up to a mentor. Focusing on the artist-at-work, McCullough holds a brush in one hand and a palette covered in paint in the other. His brush is applied to what appears to be a mostly finished landscape of the field in which he stands. His presence is enormous, as his frame engulfs the composition, giving us a slight nod as he eyes the viewer over his shoulder. His dark clothes are simple, a jacket and pants, and utilitarian. They keep attention on his face and his work, although his canvas is cut-off by the size of his form in the frame. With McCullough Lutz has focused more on the man than the art while Noel’s portrait, which maintains Lutz’ realistic style, is less formal. Dusendschon smokes in his studio, back to the viewer, as he works on an unfinished painting.

Lutz creates an atmosphere of sneaking up on the artist at work, as his back is turned to us and completely focused on his work-in-progress. Next to the painting we can see his preliminary sketch. While McCullough works in the Impressionist format, painting outside in the moment, Dusendschon is in his studio, with his sketches and tools at hand. We can see the door to his studio ajar behind him and his posture, unlike McCullough’s, is looser and unbothered as he smokes his cigarette. Wearing dark pants and a black sweater buttoned over a collared shirt, one may think the uniform of the artist is black clothes! This more “dressed up” look suggests Dusendschon crept into his studio between classes to work, a moment of inspiration, grabbing a smoke break at the same time.

How does Lutz portray the artist at work? Solitary in their studio (whether indoor or outdoor), these artists are separate from their predecessors who formed guilds to ensure quality in the finished product and an adherence to base standards. Masters trained apprentices in the arts of sketching, drawing, painting, and printing, similar to going to art school. Though art society’s in the 18th and 19th centuries determined what constituted art, maintaining a hierarchy of importance based upon consideration of skill and training, today an artist is free (and encouraged!) to play with the rules. So, the next time you find yourself in front of an artwork, whether functional or fine, consider the labor that went into creating the piece. How long do you think the artist spent on it? Was it made by a lone artist or a team (like a work of glass)? Labors of love, what do you think the artist wanted you to take away from their work?

Speaks perfectly to me ☺️ being a figurative painter myself, my first love and passion is figurative . Thank you for pointing out that there is thought and time and s piece of ourselves that go into each painting . love these works !