Charles Shepard, FWMoA President & CEO

For the past week, I’ve worked on text to accompany an upcoming exhibition, The Year of Making Meaning, which Associate Curator of Special Collections & Archives Lauren Wolfer and I have put together. This annual exhibit is intended to highlight a selection of the artworks that the Museum has acquired over the past year for the Permanent Collection. The basic idea is to give everyone in the community an opportunity to see, firsthand, the wide range of art that has recently been added to our ever expanding Collection. But, more importantly, this year it’s a chance to see a large and diverse group of work by artists that you might never have heard of before. And why is that, especially considering that the work of each of these artists has been deemed worthy of inclusion in our Museum’s Collection? Essentially, because the history of art encompasses so many artists that only the most highly regarded of them end up in the pages of our art history books. Wait – don’t I mean the most highly talented? Actually, no. Let me be quite clear that while artistic talent is generally evident in the works of those artists that grace the pages of books such as Helen Gardner’s Art Through the Ages or H. W. Janson’s History of Art, it is not historically or currently the defining characteristic that makes this artist or that a likely subject for inclusion in books such as these. Consider, for a moment, that the first three editions of Janson’s thousand page tome mentioned no women artists whatsoever. That the well-educated Janson knew of no talented women artists is highly unlikely; it is more the case that he didn’t regard them as sufficiently important to his version of the history of art. A more specific, non-gender-based slight was Janson’s exclusion, for years, of the renown Regionalist painter Grant Wood, a teaching colleague of his at Iowa University, whom he simply disliked. As these two examples indicate, there has long been a degree of unacknowledged subjectivity at work in the process of deciding who will be included in the canon of art history. To be fair, the number of artists in the world has grown exponentially in the last hundred years, and no single book or database can be expected to record the name and story of every artist who ever wielded a brush. I understand that. But I will confess that it breaks my heart when, for example, a highly skilled 20th century artist like Lili Réthi, a former member of the Royal Society of Arts who was featured in a major exhibition at the Met in 1943, is eventually forgotten. At an auction earlier this year, I was the only bidder for a wonderful, historically significant lithograph by Lili of construction workers pouring a footing for the World Trade Center in 1969. When the hammer came down, the Museum added Lili’s work to our Collection for a whopping $74! On the one hand, how sad that no one tried to outbid me but, on the other hand, how grand that Lili’s work is now in an institutional collection and will be seen by thousands of people. This piece is included in the soon-to-open Year of Making Meaning exhibition; so, her talent will not be forgotten.

Or what about another forgotten artist by the name of Louis Conrad Rosenberg? An esteemed member of the Philadelphia Society of Etchers, the Chicago Society of Etchers, and the British Royal Society of Painters, Etchers, and Engravers who consistently won prestigious awards and honors in the 1930’s. Rosenberg is virtually unknown today, even to those in the world of etchers and engravers. But nine examples of his pristine work are now in the Museum’s Collection after I discovered them at yet another auction and paid but $55 for each of them. Several of these grand etchings are also in the Year of Making Meaning exhibition.

Art history certainly remembers the famed Modernists Picasso and Modigliani, but what page or paragraph is devoted to their close friend and Modernist colleague, Carlos Mérida, of Mexico? Considered the most important abstract artist in Mexico in the 1930’s, Carlos had trained in Europe and exhibited all over the world. But by the time Abstract Expressionism took the art world by storm in the 1950’s, Carlos was essentially forgotten by the same artworld that had celebrated him just two decades earlier. I had the good fortune to find a very nice serigraph by Carlos this past year in a Texas estate auction and scooped it, unchallenged, for our Collection; and you will find it in our exhibition.

There are a number of other “forgotten” artists whose excellent works I have added to the Museum’s Collection this year. I’ve made a concerted effort to fill in some of the blanks in the art historical chronology of our Collection and, at the same time, shine a bit of light on a greater number of fine, formerly forgotten, artists. In the Year of Making Meaning exhibition you’ll see work, for example, by Doris Lee, the American Scene painter, who completed murals for the US Postal Service, did numerous covers for LIFE magazine, and won the Carnegie Prize in 1944. We added one of her wonderful rural landscapes to the Collection earlier this year that is just as strong as any by her American Scene colleague, Thomas Hart Benton.

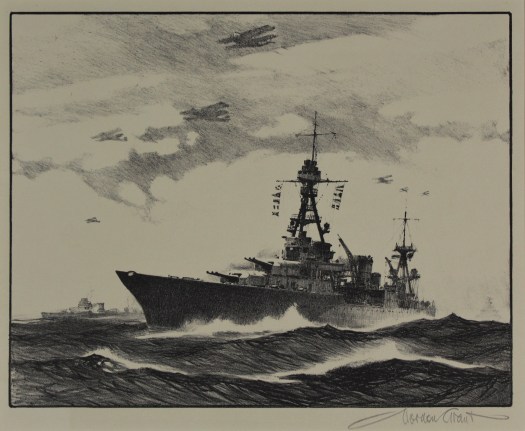

You’ll also see work by the great marine artist, Gordon Hope Grant, who received awards from the American Watercolor Society, the Salmagundi Club, the New York Society of Painters, and the American Federation of Artists. I’m sure Gordon never thought he would be forgotten back in 1906 when his painting of the warship, the USS Constitution, was purchased for the White House collection to be installed specifically in the Oval Office, where it hangs still.

Like Gordon Grant, printmaker Kerr Eby was well known in the galleries of New York in the early years of the 20th century. Eby soon became even more highly regarded when he became a combat artist in WWI and produced drawings which depicted both the horror and drudgery of war. In WWII, Eby was embedded with the Marines in the South Pacific, where he did some of his very best work. But America’s taste for Eby’s combat pictures faded quickly after the end of the war, and he came back from the war too ill to produce new work. Ironically, Eby died less than a year after WWII ended, of a tropical disease that he contracted while with the Marines. By the time Andy Warhol entered art school in Pittsburgh, Kerr Eby was but a footnote in the history of art.

Another under-rated artist in the exhibition, Irving Amen, had an auspicious start in art: he learned to draw at four and, by age 14, his talent was so advanced that the Pratt Institute awarded him a scholarship. After finishing his studies, he served in WWII for three years and, upon his discharge from the Army, he began creating work, woodblock prints, for a solo show at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. After that success, he traveled the world showing his work and returned home to teach art at the University of Notre Dame. To most of us, Irving’s career trajectory looks pretty impressive. But, perhaps because he favored printmaking, or maybe because he was an excellent teacher dedicated to his students, he gradually slipped beneath the surface of the “sea of artists” and disappeared.

That image best captures what happens to so many talented artists who, like Doris Lee, Gordon Grant, Kerr Eby, and Irving Amen, start strong and achieve considerable success but, for various reasons that have nothing to do with their talent, gradually sink beneath the waves. Maybe that’s simply fate; but, maybe it’s more a function of society’s prioritization of market value, which encourages us to remember those artists with consistently high market values and forget others that don’t.

Having said that, I will freely admit that one of my favorite curatorial endeavors is to deep dive beneath the surface of those waters and see who I can discover. Practically speaking, I do that by watching hundreds of auctions a year and trolling for great work that my research shows as under-appreciated and under-valued. I knew something about Doris Lee, for example, from past collecting, so that was just a case of waiting until something wonderful by her emerged. But Lili Réthi was a totally new discovery! The work offered at auction was compelling, so I chased it, but it took me days to research who she had really been as an artist. From a curator’s perspective, it’s like mining for gold: when you find a nugget it’s certainly rewarding for the Museum and, ultimately, the artist. As a Museum, we’re committed to building a Collection that addresses the full evolution of art in America, not just the “stars” who populate the auction houses of Christie’s and Sotheby’s and the galleries of every other museum around the country. Of course every museum has a Warhol, a Picasso, a Pollock. Congratulations. But not every other institution has a Lili Réthi or a Doris Lee or a Kerr Eby. I’m proud that our Museum has many of the “names”, but I’m even more proud of the fact that we have great art by some artists who were simply forgotten by a market system that let them slip beneath the waves.

To get a better sense of what I’m talking about in this post, come on down to the Museum and spend some time looking at the “gold” I’ve discovered in the sands beneath those waves. I promise that you’ll be glad you did.

A Year of Making Meaning opens this weekend, Saturday, October 24th and runs through January 31, 2021.

2 Replies to “Off the Cuff: The Forgotten”